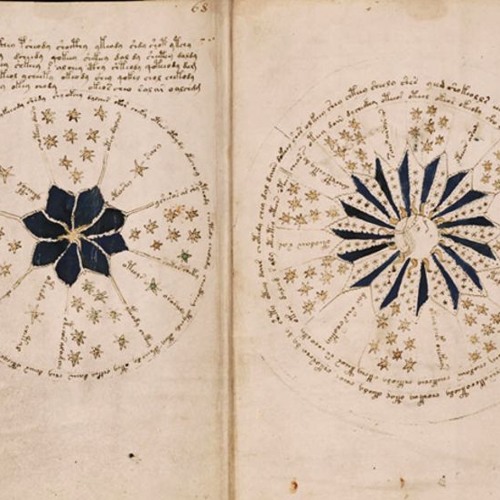

The manuscript’s “botanical drawings are no less strange: the plants appear to be chimerical, combining incompatible parts from different species, even different kingdoms.” These drawings led scholar Nicholas Gibbs, the latest to try and decipher the text, to compare it to the Trotula, a Medieval compilation that “specializes in the diseases and complaints of women,” as he wrote in a Times Literary Supplement article earlier this month. The manuscript’s origins and intent have baffled cryptologists since at least the 17th century, when, notes Vox, “ an alchemist described it as ‘a certain riddle of the Sphinx.’” We can presume, “judging by its illustrations,” writes Reed Johnson at The New Yorker, that Voynich is “a compendium of knowledge related to the natural world.” But its “illustrations range from the fanciful (legions of heavy-headed flowers that bear no relation to any earthly variety) to the bizarre (naked and possibly pregnant women, frolicking in what look like amusement-park waterslides from the fifteenth century).” Scholars can only speculate about these categories. “Over time, Voynich enthusiasts have given each section a conventional name” for its dominant imagery: “botanical, astronomical, cosmological, zodiac, biological, pharmaceutical, and recipes.” A comparatively long book at 234 pages, it roughly divides into seven sections, any of which might be found on the shelves of your average 1400s European reader-a fairly small and rarified group.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)